Harmonic Syntax

To this point in the course, you as students have had very limited control over composition tasks. In most cases, the choice of what chords were to follow from each other was not yours to make. Instead, you were given a pre-composed chord succession, usually as a string of root letter names (C-F-G-C) or Roman numerals (d: i iv V i).

Having now surveyed the types of chords that can be expected in major and minor pieces, it is now possible to introduce the concept of chordal syntax. Doing so will give us a means for discussing how chords should be ordered in composition.

What is Syntax?

SYNTAX is a word that is used to describe languages. Specifically, it refers to the rules for ordering the words within that language to create logical sentences. Below we have two sentences in English. The first obeys the rules of syntax, and the second one breaks them.

Sentence 1: The green car sped around the corner and out of sight.

Sentence 2: Sped the car green corner the around of sight out and.

Even without Sentence 1 present, we might be able to guess at the meaning of Sentence 2, but it would take a lot of work. The nouns, verbs, and prepositions do not line up with our expected word ordering rules for English, which is, roughly as follows:

The formula given above explains why Sentence 1 sounds right to English speakers and why Sentence 2, though comprehensible, sounds wrong.

In music, the issue of syntax applies a bit differently, since there is no direct parallel to a “literal” sentence as from a spoken language. True, a musical phrase communicates a full musical thought. But the notes of a phrase do not relate a specific event such as a car speeding, or a girl catching a ball.

Due to this, the issue of how syntax applies to music is a bit looser. Every musical style (or, if you prefer, dialect), such as Rock, Classical, Jazz, has its own expected formulas for chord progressions, which can be communicated in strings of Roman numerals. When the syntax is followed, the resulting music sounds like it belongs to the style. When it is not, the music sounds like it doesn’t fit the style.

Classical Syntax

The musical style that this class has been rooted in is Classical music, which developed originally in Western Europe roughly from 1700-1825, though it soon was adopted in many other parts of the world and is still widely in use today in movie music and advertising jingles. Closely wedded to the notion of “good chord choice” in classical music is the idea of Progression. For a phrase to sound good to a Classical listener, it should start on a tonic (I) chord and constantly move forward towards a cadence that is expected within 4-8 bars.

This brings up the question: how does one make music sound like it is moving forward, harmonically? In preparation for answering this question, we must first introduce the concept of chord root motion.

Root Motion Types

We return one last time to the idea that only seven letter-name and seven basic triads exist. Excluding the unison/octave, that means that only six intervals exist among roots. For convenience, we will group them further into three basic root intervals, which can occur either in an upward or downward direction:

Motion by Step: for example I-ii, iii-IV, vi-V

Motion by Third: for example I-iii, iii-V, vi-IV

Motion by Fifth: for example V-I, ii-V, I-IV

(Note that 1. Any measuring arrow at right can be shifted to start on any Roman numeral, and 2. Interval size is counted as before. The distance from I-iii involves three different number names (“I, ii, iii”) and is therefore a 3rd.

Readers will note that this is a much simpler system than the one given in Unit 4. Where earlier, we were concerned with all types of intervals, 2nds-3rds, all the way up to 7ths, now we are limiting ourselves just to 2nds, 3rds, and 5ths. To determine the interval between two chord roots, one can read the chords in terms of their Roman numerals or letter name root and then determine the most direct path between them. Here are three examples of this process, worked out:

Notice that for some of the chord pairs above, one or more of them appear in inversion. This makes no difference at all for measuring the harmonic interval between them.

Preferred Root Motions

The three strongest, most directed root motions in classical music are as follows:

1. Descending Fifth: The descending fifth motion is a very common progression in many styles. From whatever chord you are in in a piece, it is always possible to descend by 5th the following chord (or, progress counter clockwise around the circle of fifths). Here is the full string of descending fifths, which connects a tonic to itself with all strong motions.

A Circle of Fifths: I – IV – viio – iii – vi – ii – V – I

Same thing in C major: C – F – bo – e – a – d – G – C

In fact, many pieces are based entirely on this chord pattern, including “Fly Me to the Moon” and the chorus of the children’s song, “B-I-N-GO”.

In fact, this progression is so ubiquitous, a crafty youtuber has created a 35-minute mix of descending fifth progressions!

2. Ascending Step: Ascending steps often provide a moment of upward tilt during a phrase. The most notable ascending step motion is from IV-V near the end of a phrase. Other common ascending steps involve I-ii or V-vi. Below, we show the ascending step within a Bach chorale progression using an upward-tilting line:

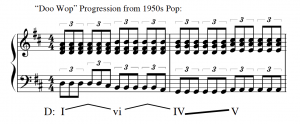

3. Descending Third: A descending third can be thought as covering half the ground of a descending fifth. It is thus similarly directed, but a bit less powerful. Descending thirds often are strung together, connecting tonic (I) all the way to a ii or IV chord that will then proceed to V to mark the end of a phrase in some way. This is exactly what happens in the “Doo Wop” progression that was ubiquitous in 50’s pop:

A great example of this progression is in “Those Magic Changes” from Grease:

Other Good, but non-Directed, Motions

In addition to the stronger root motions noted above which push the phrase forward, there are a number of “holding pattern” progressions. These chord formulas typically involve alternation between two chords. They can go on for quite some time. I – IV – I (– IV – I – IV – I – as desired) I – V – I (– V – I – V – I – as desired)

An example can be seen right at the beginning of the Finale (Presto) from Beethoven, Symphony No. 5–it’s a phrase built out of only I and V:

A Global Model for Classical Chord Progression

The following diagram encapsulates all of the points made about chord progression above. By following the arrows, you will quickly be able to generate classical-sounding phrases. This, of course, is not the method that experienced composers use to write music, but it allows you to begin exploring how harmonies can work together to create harmonic progression.

A few important points to note about this chord chart

- The tonic, I, may move to any chord! These arrows are omitted only to avoid cluttering up the diagram.

- Harmonic progressions are shown at left. The two “holding patterns” are shown at right. Chords may toggle back and forth as many times as desired.

- The backbone of the PROGRESSION area, moving from left to right, is descending fifth motion. iii-vi, vi-ii, ii-V, and V-I are all examples of D5 motion.

- Within any box, the two chords are related by thirds. It is always better to move by descending third motion, particularly for IV-ii.

- Notable ascending 2nd motions are shown from iii-IV, IV-V, and from V-vi.

- The diagram applies to minor keys as well as major.

Other Chord Models from Other Musical Styles

In this class, we will not have the opportunity to explore other styles of music. You should be aware, though, that chord progressions vary tremendously among different types of music. In fact, a motion that sounds perfect in one style can sound completely strange, like a mistake, in another.

Consider the case of V-IV. This is considered a “retrogression” (backwards motion) in classical music, and is often marked wrong in theory classes. Yet this motion is absolutely stylistic to blues, jazz, and rock. In the standard 12-bar blues progression, shown below (each Roman numeral represents a measure of music), the V-IV motion occurs in mm. 9-10 in what could be considered the essential “cadence” of each blues phrase.

I I I I IV IV I I V IV I I (or V)

Famous examples of 12-bar blues: “Rock around the Clock” (Bill Haley) “Johnny B Goode” (Chuck Berry) “Rock and Roll” (Led Zeppelin) Countless other examples of chord motions can be found that are commonly used in rock and roll but not in Classical music. Rock often even uses chords with roots outside the traditional Classical gamut, namely the bVII (lowered seventh) chord. (The “Na na na” chorus from “Hey Jude” (Beatles) uses a bVII – IV – I over and over).

Composing with Frequently-Used Chord Successions

Of all the progressions in Classical music, where do most I chords go? Given all the progressions in Classical music, what would be a surprising chord to follow a V triad?

When you ask questions like this, you’re framing chord progressions in terms of their probabilities or frequencies. If we want to write a very expected or normal chord progression, we would simply look for chord progressions that occur most frequently –are most probable– in some repertoire of music. If we want to write a surprising chord progression, we would look for progressions that occur very infrequently in that repertoire. The chart that follows shows how often each succession of chord roots occurs in a dataset of Classical music (the dataset is described here):

We read the table by considering the left-hand column to indicate the first chord in a chord progression, and the top row to indicate the second chord. (A ii chord moves to a V chord 72% of the time: that value is in the fifth column of the second row.) Each row adds to 100%. This means that we can read each value as something like, “Of all the first chords in this dataset ___% go to second chord.” (i.e., “Of all the ii chords in the dataset, 72% go to V chords.”)

Looking at the chart, we can see that progressions that follow the above global model (like I-IV-V-I or vi-ii-V-I) get high percentages (i.e., high probabilities), while progressions that do not follow the global model (like vi-iii-vii-ii) have very low percentages. In other words, the global model is captures tendencies and frequently-used progressions and excludes those progressions that don’t happen very often.

A benefit of thinking about harmonic syntax in this way is that we can easily compare styles. The chart below now shows the probabilities of two-chord successions in a pop/rock dataset (described here):

Notice that some progressions that almost never happen in the Classical syntax happen in the pop/rock syntax: while V-IV happens very little in the Classical table (7%), it happens a reasonable amount in the pop/rock table (28%).

We can use these concepts to create our own chord progressions, relying on frequent/probable progressions for most our our successions, but using infrequent/improbable progressions to create moments of surprise. At this website you can create your own progressions in the key of C as the interface shows you a) the progressions’ probability in real time and b) other pop songs your progression is used in!

A great example of using low probabilities for effect is in the very first phrase of “Somewhere Over the Rainbow.” Judy Garland’s character sings “Somewhere over the rainbow…” over a tonic triad (“Some”), a vi triad (“where”) and a iii triad (“over the rainbow”). Looking at both the Classical and pop/rock tables, the move from vi to iii (an ascending fifth!) happens quite infrequently in these repertoires. And so, that chord change adds a surprise and poignancy to support the longing lyrics.